In the end, Emma Goldman never said “If I can’t dance, it’s not my revolution”, though it’s a great maxim and she could definitively have said it. What she did say was much more interesting.

Her story begins when she arrives in New York City in 1889 as a 20-year-old with three countries, an authoritarian father, and a failed marriage behind her. She had few dollars in her pocket and carried an ideal in her mind — anarchism. She had been drawn to anarchism by example of the “Chicago Martyrs”, the labour organisers falsely accused and executed in 1886 for a bombing at Haymarket Square, where a crowd was gathered, demonstrating for the right to an eight-hour workday.

She had a sewing machine that had been sent to New York City in advance — not a detail, but a tool for material autonomy and personal liberation. Back then, when marriage or becoming a server maid were two of the most common paths for women, the ability to operate a sewing machine gave a young woman like Emma Goldman the opportunity to earn just enough to rent a room in the Lower East Side of Manhattan and afford basic necessities.

On her very first day in Manhattan, she found her first mentor, the actor and publicist Johann Most. At Sachs Café, the meeting place for Yiddish-speaking anarchist in Lower Manhattan, she met her future lover and lifelong friend, Alexander Berkman, during a late-night dinner during which he ate prodigious amounts of food.

Shortly after that, Emma Goldman got herself a place to stay: “I found a room on Suffolk Street, not far from Sachs’s café. It was small and half-dark, but the price was only three dollars a month, and I engaged it”. And so began Emma Goldman’s real life, the one she described in her nearly thousand-page autobiography, Living My Life, one of the most fascinating books about the trajectory of youth at the turn of the 19th to the 20th century and their experimentations with anarchism, socialism, feminism, free love, freedom of expression. This work and Emma Goldman’s journal which she would rename Mother Earth were the beginnings of what we would come to call political ecology.

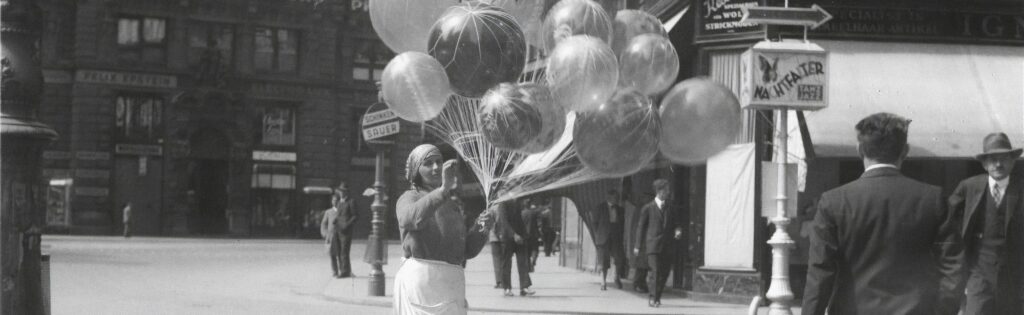

Emma soon became active in anarchist immigrant circles, helping produce periodicals and making speeches (mostly in Yiddish in the beginning; gradually more in English). She was also having a great time; she was living with Alexander Berkman, whom she always called Sasha, and other friends, both male and female, in a communal apartment, going to the theatre, and enjoying the bohemian life.

And that’s when it happened, as she tells in Living My Life:

“At the dances, I was one of the most untiring and gayest. One evening a cousin of Sasha, a young boy, took me aside. With a grave face, as if he were about to announce the death of a dear comrade, he whispered to me that it did not behove an agitator to dance. Certainly not with such reckless abandon, anyway. My frivolity would only hurt the Cause.”

“I told him to mind his own business. I did not believe that a Cause which stood for a beautiful ideal, for anarchism, for release and freedom from conventions and prejudice, should demand the denial of life and joy. I insisted that our Cause could not expect me to become a nun and that the movement should not be turned into a cloister. If it meant that, I did not want it. ”I want freedom, the right to self-expression, everybody’s right to beautiful, radiant things.”

This was the birth of her most famous phrase, the one she never said: “ If I can’t dance, it’s not my revolution.”

Emma Goldman’s reaction was not a belated response to the development of authoritarian socialism in the USSR which she came to know well when she lived there for two years between 1919 to 1920. She had listened in astonishment to Lenin and other leading Bolsheviks repeating that “freedom of speech is a bourgeois superstition” to her, who had been repeatedly imprisoned and then deported for exercising that very freedom of speech in the capitalist USA. The episode in which the famous apocryphal phrase was inspired happened more than 20 years before. It was more an early reaction to the propensity of progressive and revolutionary men to pontificate on the behaviour of their female coreligionists, a tendency that justified the birth of a properly feminist political theory, distinct from that of progressive male thinkers.

More importantly, Emma Goldman did not express her fundamental creed in purely negative terms (not my revolution). Rather, she expresses it in a positive sense, as objects of political desire, “I want freedom, the right to self-expression, everybody’s right to beautiful, radiant things.”

This is perhaps one reason why Emma Goldman’s book is not taken as seriously as the thick political theory tomes of her contemporary male counterparts. Rather than dry, abstract argumentation, Living My Life is full of reflections on theatre and opera, literature and music, falling in and out of love.

Emma Goldman not only describes the kind of revolution she does not want but also the kind of society to which one should aspire. It’s about things yes but also beauty and the liberation of potential — hence her use of this fascinating word, “radiant” — i.e., objects of political desire.

Emma Goldman can be considered the last great feminist before modern feminism. In this sense she shares the fate of other 19th- and even 18th-century authors, such as Flora Tristán, Leonor da Fonseca Pimentel, Mary Wollstonecraft and Olympe de Gouges. These women had in common not only their indomitable courage against persecution or their steadfastness in the face of social and political disapproval, including from their fellow revolutionaries. They understood that a just society is more than a society without injustice. A just society must be a desirable society, one where people can pursue their desires and collectively flourish.

(Article published in the Green European Journal, 29 January 2023)